Canada’s economy has always been closely linked with its resource sector. Long referenced as “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” our use of natural resources since long before the country’s inception is well documented. While that description is pretty accurate, there is a strong case that “diggers of stuff” could also be added to that old trope.

Canada is one of the world’s largest mining nations, ranking among the top five in 13 major mineral and metals categories. According to the Canadian Minerals and Mining Plan, a joint initiative between federal, provincial and territorial stakeholders to “solidify Canada’s position as a mining leader,” some 200 mines and 7,000 quarries in 2016 produced more than 60 minerals and metals worth $41 billion. That’s a lot of digging!

But the question remains, what happens to these mines when they are exhausted of their riches? Apparently not a lot. According to a 2007 McGill University study there could be more than 10,000 abandoned mines throughout Canada, with more than half of those in Ontario.

The city of Faro

The city of Faro

Enough abandoned mines have already been identified that the people tasked with cleaning them up, or remediating them will have their hands full for a very long time. And, the job of cleaning up, or remediating, all of these mines will be exceedingly difficult. How difficult you ask? Well…

The Faro Mine is one such case. Located in south-central Yukon, near the town of Faro, the mine began operations in 1969. It was one of the world’s largest lead-zinc mines – it was at one point the largest open-pit mine on the planet and accounted for 40 percent of Yukon’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Tough times came to Faro in 1982, when world metal process plummeted, and by 1998, after a succession of bankruptcies and mergers, operations ground to a halt and the mine was abandoned. Not only did this devastate the local economy, but the abandonment left hundreds of millions of tonnes of tailings and waste rock ready and waiting to turn into an environmental mess.

There was a longstanding program to try to find the reclamation solution for Faro, and it has been a very long process with many different groups involved

Currently, the federal government has ownership, and spends roughly $40 million per year just to keep the pumps running and the tailings dam performing as required – it hasn’t even started remediation yet and doesn’t anticipate starting the job until at least 2023. In fact, the Faro Mine has been called: “one of the most complex abandoned mine remediation projects in Canada.”

When remediation eventually begins, Ecometrix, a Toronto-based firm that specializes in environmental intelligence, will have played an important role. Ecometrix combines science, engineering and technology to assess and solve complex environmental challenges. It just so happens that finding solutions for managing the effects from abandoned mines is exactly that kind of challenge.

“There was a longstanding program to try to find the reclamation solution for Faro, and it has been a very long process with many different groups involved,” explains Ron Nicholson, former senior environmental scientist and Principal of Ecometrix.

He says there is now a proposal for reclamation of the site, and in that process, there’s a requirement for an environmental assessment with the Yukon Environmental and Socioeconomic Assessment Board (YESAB). Ecometrix is helping YESAB evaluate the very dense technical and scientific aspects of what is likely to be a multi-year process.

When an environmental assessment is completed for an operation, stakeholders must examine the possible effects the project will have on the environment, on human health, and also the social effects – such as the economic impact on surrounding communities.

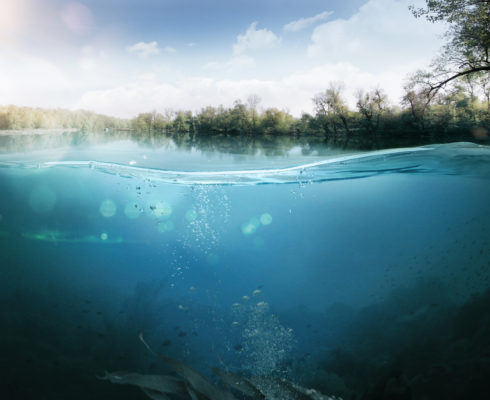

“There are a number of different areas that have to be looked at in terms of the environment of a project like the Faro Mine remediation, and a big one is water quality and quantity, and what effects there are going to be from the project on the local and downstream water,” says Nicholson. Although Ecometrix’s focus will be on water and aquatic resources, Nicholson points out that the environmental assessment also considers many more aspects of the project including effects on the communities and wildlife in the surrounding region.

It's important to note, this assessment is being conducted on the proposed remediation work that is meant to stave off the increasing environmental impact that the mine represents. It will not address all of the current impacts of the Faro Mine itself.

“That’s what makes understanding what exactly is being assessed difficult.” On the one hand, the Faro Mine is not a greenfield site, so there are already environmental effects. “We have to understand the purpose of the project. Is it to get back to pre-mining conditions or is some long-term level of change acceptable? I think a complete clean-up of the site would be impossible to do in an economical way. Basically, the work is being assessed to decide if it is going to make the situation better,” he explains.

How do mines like Faro become environmental problems?

When companies want to extract the economic minerals from ore, they typically scoop up the mineral-rich rock and pulverize it to a very fine consistency, similar to beach sand. They can then extract what they want (at Faro it was zinc and lead) and what’s left over becomes tailings. Tailings are essentially the ore with the economical minerals removed. Some of the rock that lays between the miner and the ore body, the waste rock, is also extracted and must be managed.

Abandoned open-pit gypsum mine in Canada

Abandoned open-pit gypsum mine in Canada

The problem with some ore deposits is that they contain materials that react with the environment. For example, some non-economical materials such as sulphide minerals, become acidic when exposed to air. It’s like when you cut an apple, the inside will turn brown when it’s exposed to air. When these materials acidify, they increase the solubility of other chemicals, like heavy metals, which enter the environment in run-off and groundwater. At high levels in the environment, these chemicals become contaminants. At Faro, these reactive materials exist both in the tailings and in the waste rock. Both of which have been acidifying since the 1970s and leaching contaminants into the land and groundwater the entire time.

Going back to the apple analogy, the key to stopping the reaction is to keep the reactive material away from the air. While a freshly cut apple turns brown quickly, immersing the apple slices in water, effectively creating a barrier between it and the air, stops the oxidation in its tracks.

“The same process of creating barriers between air and the reactive waste rock and tailings is the plan for the Faro Mine,” says Lynnae Dudley, a former environmental scientist and risk assessor at Ecometrix.

“That will halt the generation of future contamination, but they still must deal with all of the water that has already been impacted over the years and is now caught up in the materials and groundwater at the site. At Faro, they have a great big open-pit that they can pump the contaminated water into. The plan is to use the pit to manage the contaminated water on the site so they can treat it before it’s released to the environment,” she says.

Looking at a challenge from many different perspectives is fundamental to bringing environmental intelligence to decision making. Our team welcomes the chance to participate in the process.

It sounds simple, but it is not. Dudley explains that even after the contaminated areas of the site area are covered, there will be a lot of management required to meet the remediation objectives for the project.

“That’s one of the key aspects we’re looking at. Since water management is the main issue, we want to be sure they will be able to collect and divert all of the contaminated water to the pit without it, say, escaping underground in the groundwater. Can they manage to minimize how much water they have to manage, and can they collect all of the contaminated groundwater?”

The work being done during the environmental assessment will be essential to the ultimate success of the project. “In our line of work,” says Dudley, “looking at a challenge from many different perspectives is fundamental to bringing environmental intelligence to decision making. Our team welcomes the chance to participate in the process.”